Haven't We Seen This All Before?

“Fashion’s problem isn’t the algorithm 'slop'. It’s us.”

Disclaimer: The following contains strong opinions, mild despair, industry in-jokes, and an unshakable love for fashion buried beneath layers of sarcasm. If you’re easily offended, work in PR, or recently paid $1,200 for a “quiet luxury” hoodie, proceed with caution. Then again, you’ve seen me say all this before.

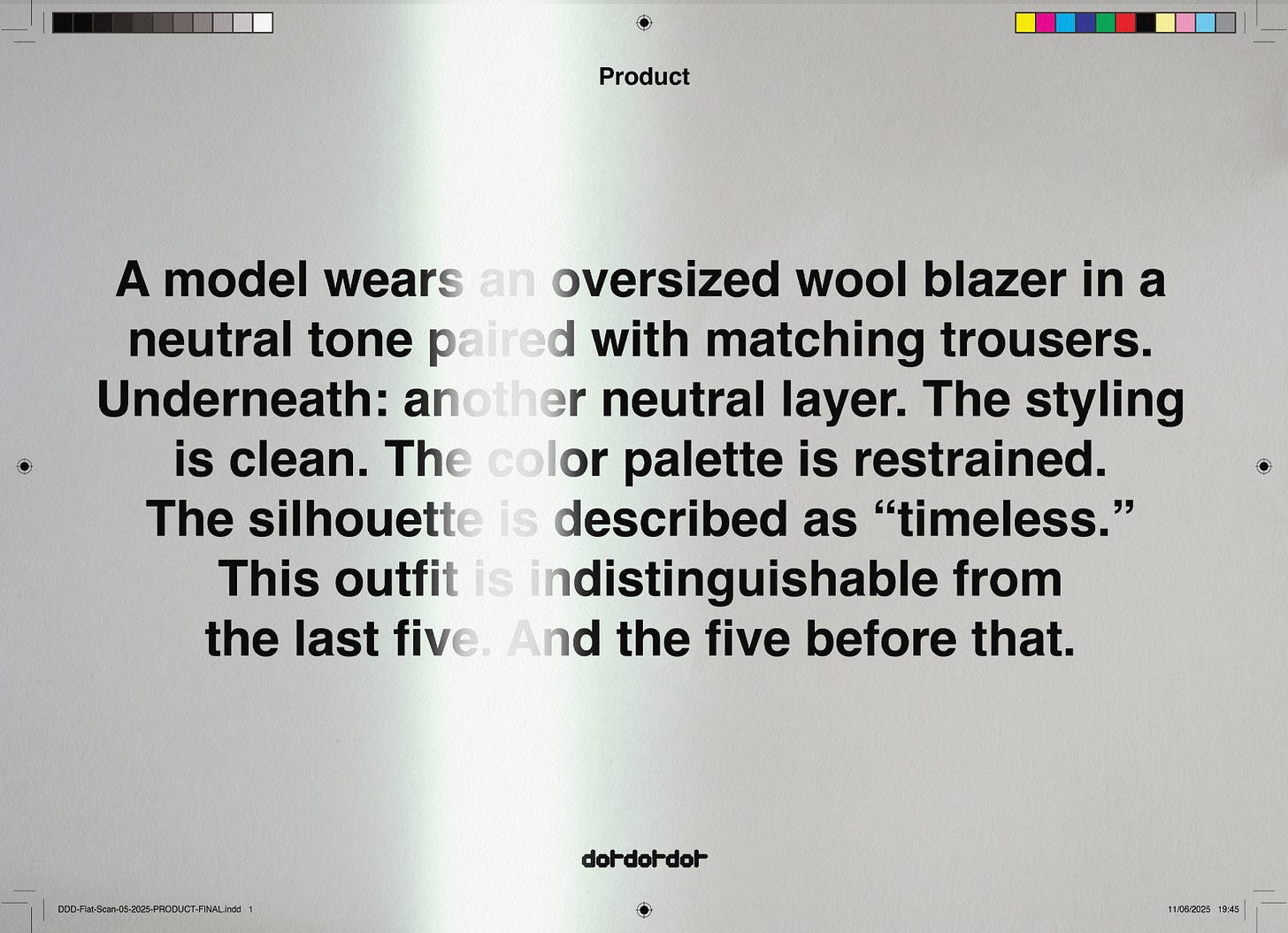

In the $1.8 trillion fashion industry, everything looks the same now.

Not because we’ve run out of ideas, but because we’ve run out of incentives to do anything different. The silhouettes are oversized. The palettes are neutral. The mood is moody. The campaign features a model who looks like she’s just remembered she signed a five-year contract with no exit clause. The backdrop is either a field, a stairwell, or a brutalist playground that no child has ever touched.

At this point you could be looking at Zara or Loro Piana. The distinctions are aesthetic illusions.

We’re living through the reign of Template Chic: a global style consensus built on recycling the last thing that worked. Not because people don't care, but because the industry stopped asking them to.

This is not an outsider’s critique. I’ve been in the rooms. I’ve sat at the free dinners, worn the free clothes, flown out for previews, been briefed on “the vision.” And I’ve smiled through the same euphemisms every year: “We’re refining the DNA,” “elevating the proposition,” “tapping into the new wardrobe for the modern woman.”

Most of the time, they don’t know what they’re saying. The ones who do? Their vision gets watered down until it tastes like every other collection in Paris.

And yet, the best brands resist this erosion. They speak with clarity, even if softly. They don’t design for consensus. They design for conviction. They trust the audience to catch up, or not.

The System Is the Problem

If the aesthetics feel flat, it’s because the structure is hollow. The sameness we’re seeing isn’t just the fault of brands, PRs, or fashion magazines but the direct result of a business model that prioritizes speed, volume, and scale over originality.

The major conglomerates that now dominate fashion operate at the pace of the feed. The production schedule once reserved for ultra-fast fashion has been adopted by the very houses that used to define slow, deliberate luxury. Designers are no longer creators, they’re content engines.